One of Baltimore’s reasons for success in last week’s Wild Card bout against the Pittsburgh Steelers was the defense’s ability to make the Steelers’ offense one-dimensional.

Having star running back Le’Veon Bell on the sidelines heavily aided the Ravens’ efforts, but just because Bell was absent did not mean Pittsburgh would not be able to run the football at all. For most of the game, though, the offense simply could not, more because of Baltimore’s stout run defense than the loss of Bell.

No Steelers ball carrier finished with more than 25 yards on the ground (Josh Harris had 25 yards on nine carries) and in total, the three Steelers running backs – Harris, Dri Archer and Ben Tate – finished the game with 15 carries for 43 yards and zero touchdowns.

The inability to get the ball moving on the ground forced the game into quarterback Ben Roethlisberger’s hands, as he attempted 45 passes on the night, 16 more than his opposite number, Joe Flacco.

Roethlisberger completed 31 of 45 passes but also had two interceptions; many of his completions came as a result of Baltimore’s “bend but don’t break” defense. If the Ravens defense can eliminate the run, playing conservative coverage to take away the deep pass but allow easy throws underneath is a favorable tradeoff.

Baltimore’s stout red zone defense allows it to buckle down when it needs to, often holding the opposing offense to just a field goal during scoring opportunities.

On Saturday against the New England Patriots, the story needs to be the same. Eliminating New England’s 18th-ranked run offense will force the game onto the shoulders of quarterback Tom Brady. If the Ravens can do that, they can afford to let up the simple passes, as long as they do not get beat deep.

Making the Patriots one-dimensional will be the first key to success when it comes to stopping Brady. In Baltimore’s three playoff games at New England under John Harbaugh, Brady has just three touchdown passes but has thrown seven interceptions. Unsurprisingly, the Ravens have won two of those games.

The Ravens have had success against Brady more often than not, and a strong performance by the run defense will only help the cause.

Let’s take a look at Baltimore’s dominant run game and how it shut down Pittsburgh’s rush offense.

Baltimore’s best asset when it comes to shutting down the run is second-year nose tackle Brandon Williams. Turning into a force as a run defender, Williams singlehandedly impeded several Pittsburgh run plays.

Williams has been anchoring the run defense all season and the playoff game against Pittsburgh was no different.

Often a disruptor to cause chaos and allow other Ravens defenders to make plays, Williams is no slouch when it comes to making unassisted stops.

Against Pittsburgh center Maurkice Pouncey, Williams had little trouble getting off blocks.

On a run to the outside right, Tate has two run lanes to choose, but the inside lane is an intriguing one with an initial clear path.

Tate notices this and chooses the lane to his left, however Williams’ presence causes trouble. While Pouncey holds his own against Williams in the beginning of the play, the strength of the nose tackle proves (as it often does) to be too much.

When Tate makes the cut back, Williams has already disengaged from his blocker.

The massive size of Williams instantly clogs up the run lane, leaving Tate with nowhere to go. As the lone defensive lineman in position to make the tackle, Williams answers the call and stuffs Tate in the run lane to allow only a minimal gain.

Williams has been a dominant run defender all season and that did not change so far in the playoffs. Furthermore, his disruption inside is enhanced with the return of Haloti Ngata. Throw in the potential return of rookie Timmy Jernigan and Baltimore’s interior run defense will be hard to get by in New England.

But if the Patriots do manage to sneak past the first line of the defense, it will not necessarily mean success. While Baltimore’s defensive front is often the difference maker against the run, the linebacker corps often does its job.

One linebacker who plays the run well is rookie C.J. Mosley. He has the downhill ability to shoot through a gap and make a stop if needed, but is often patient enough to sit back, let the play develop and then occupy the correct run lane.

On a run by Harris, Mosley stays back and lets the run play develop.

A benefit of waiting is that Mosley can see who tight end Heath Miller chooses to block. If Miller goes outside to seal off the outside linebacker, an easy one-on-one with Harris will arise. If Miller choose Mosley, the outside linebacker could either prevent the outside run by Harris or crash in and make the tackle.

Miller spurns Mosley and opts to block on the outside, leaving the rookie as the lone defender to prevent Harris from creating anything on the run.

Once the opportunity opens up for Mosley, he closes off the gap, forces a pileup and makes the tackle.

Fellow inside linebacker Daryl Smith has also performed well against the run this season, making the second line of Baltimore’s interior run defense harder for opponents to navigate.

Getting Ngata back in the lineup was a key difference maker, but the return of defensive end Chris Canty – who missed Week 17 – was just as important against Pittsburgh. Canty was more disruptive than usual and displayed a burst when defending the run to help him make plays.

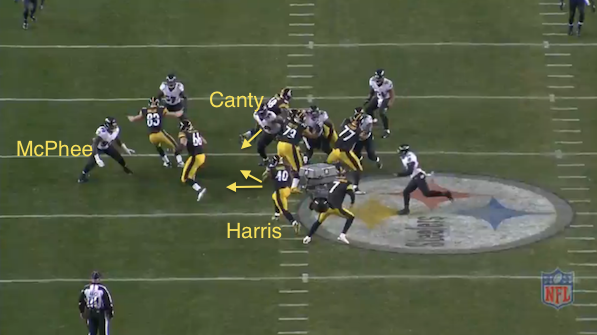

Here, Canty begins the play lined up on the opposite side of the run direction.

Whether by design or instinct, Canty’s first thought is to attack the right side of the defense, and he begins to make his way across the line as Harris receives the handoff.

The quick thinking by Canty makes it difficult for Pouncey to slow down the defender.

Without Canty making his way to the other side of the defense, Harris would have a wide-open run lane between the left tackle and tight end.

Instead, Canty’s presence seals the hole up, leaving Harris with a decision to make: attack Canty or bounce to the outside, where outside linebacker Pernell McPhee is in position to make a play.

Harris chooses the latter, which is just as tough of a run lane as the inside, as McPhee has the area sealed off.

Combine McPhee’s hold of the outside with Canty’s quick closing speed through the gap and Harris simply has nowhere to go, ultimately being brought down by the duo.

Even if the Steelers had the luxury of Bell in the lineup against Baltimore, the run defense of the Ravens would have likely outmatched Bell on most occasions.

If Baltimore’s run defense can perform this well once again (it has been dominant all season; no reason to think it will not be able to against New England) this week, it will go a long way toward slowing down the potent Patriots pass attack.

The likes of LeGarrette Blount, Shane Vereen and Jonas Gray is not exactly an imposing bunch. Having the run defense play to its capability will heavily neutralize and potentially shut down New England’s rush attack.

If that occurs, the majority of the work will come from New England’s pass offense and Brady, who had 33 touchdowns an just nine interceptions through the air during the regular season.

The Ravens have proved before that they have the blueprint to slow down the Patriots offense in the playoffs. Can they do it again?