The Beatles, for my money are by far the best band of all-time. They were pioneers, breaking down doors in America and paving the way to the British Invasion after which, music changed forever. They were trend-setters in style and in fashion and in many ways spokespersons in the 60’s for millions worldwide. But for me, the two things that set them apart from every band before or since are:

1. They, more than any other recording act, inspired more artists to become musicians, and it’s not even close; and

2. The depth, range and volume of work they created beginning in 1963 and ending in 1969, is unprecedented.

Think about this. On January 18, 1964, I Want to Hold Your Hand hit No. 1 in the States. Five years later they were in the studio recording and composing songs that would appear on Let it Be and Abbey Road. In between, they pushed the boundaries of recording and composition with LP’s like Rubber Soul, Revolver and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Consider their rapid progression in song composition and craftsmanship in such a short period of time.

Volume, quality and range in six years.

Mind. Blown.

A couple of months after The Beatles released Sgt. Pepper their manager Brian Epstein died on August 27, 1967 from an accidental overdose. The band had no real business acumen. Their talents were grounded in creating and playing music. John Lennon outwardly expressed that he thought the band was finished after Epstein’s death. Paul McCartney thought otherwise.

Paul assumed the role of musical director. He pushed the band forward, encouraging each member to continue to evolve. As the only single member of the band living in the swinging city of London while the others domiciled with their families in the suburbs, McCartney’s ambition propelled The Beatles forward. The rest of the band begrudgingly obliged, albeit with some intermittent pushback.

Five months after the release of Sgt. Pepper, The Beatles had Magical Mystery Tour ready to hit record stores. Six months later, the band started work on their next project, a stripped down, back to basics production devoid of the studio wizardry they mastered on Pepper. Instead of the complicated and colorful album jacket with imaginative titles, the name of their next LP would be simply, “The Beatles” and presented in a completely white jacket. Unsurprisingly, the album would become popularly known as The White Album.

The recording of The White Album, a double LP, was completed on October 18, 1968 and released in November of ’68. Just two months later, The Beatles prepared to take on their next project, but with a different twist. The making of their next album would be caught on film, capturing the band writing, developing and rehearsing brand new material which would later be performed live. That live performance would become their next album. It was a great concept that never came to fruition due to the incredible time constraints and creative pressures placed upon them – some of which were self-inflicted.

The Beatles got together in London’s Twickenham Studios on January 2, 1969 to begin implementation of the plan. Right off the bat the band encountered a couple of daunting challenges. First, they really didn’t have much in the way of new material and none of what any of the composers had was ready for presentation to the other band members. Their goal was to pen 14 new songs. They had none.

And as if that wasn’t enough pressure, The Beatles had to compose, rehearse, perform and record the 14 songs by the end of the month because drummer Ringo Starr was due on set to begin filming a new movie called The Magic Christian which would also star Peter Sellers and feature Raquel Welch. It was a hard deadline. Normal men would crack under such immense pressure. But there was never anything normal about The Beatles.

The film that was completed and released in 1970, Let it Be, was dark and in McCartney’s words years later, would show the world how a band breaks up. But in hindsight (thanks to Peter Jackson’s redo), the narrative which has lived for 50 years and supported by Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s visual presentation, seems forced and probably influenced heavily by the eventual demise of the band 16 months later, right around the time of Let it Be’s release.

But what really happened during that month of January, 1969 as evidenced by Jackson’s three-part documentary Get Back, was NOT the visual diary of The Beatles disintegration. That would come later when the band was fractured by the introduction of Allen Klein as the band’s new manager – a move the Rolling Stones warned The Beatles against, as did the Stones’ producer Glyn Johns.

Most of what you see in Jackson’s version of those January ’69 events is the collaborative process of four men who genuinely enjoy each other’s company. The clear takeaways are that of camaraderie, work ethic and passion. McCartney’s behavior is a bit like a Secretary of State. His is a take-charge, let’s get this done persona, all the while cognizant of the other personalities in the band. He understands that John is more invested in his love interest Yoko, than he is the band, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that Lennon is uninterested either. He’s just no longer as driven as McCartney.

Paul also understands that the grand closing to the project (concerts at an exotic amphitheater in Libya or a Mediterranean cruise ship for the live recording were suggested) must consider Ringo’s time constraints. Starr cannot entertain a trip abroad. As for George Harrison, there are moments when he and McCartney disagree but ultimately the two come to an understanding that the songs aren’t necessarily Paul’s or John’s or George’s. Instead they belong to the band and during the three-part series, despite the pressure, despite Harrison’s own ambition to become a more prominent contributor to songwriting, they come to the realization that they’re all in it together.

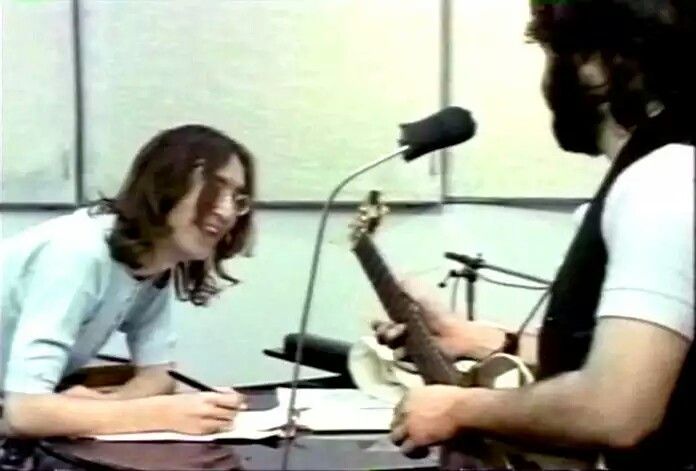

Jackson’s Get Back is the alter ego to Lindsay-Hogg’s Let it Be. We know now how the story ends, but if Jackson’s presentation was the 1970 version instead, who knows what may have ensued. Jackson shows us that the Lennon/McCartney relationship was still strong, so much so that when they share a mic, eye-to-eye while rehearsing Two of Us, the chemistry is overwhelming, particularly to Harrison who seems a bit teary-eyed. A viewer could easily draw the conclusion that the Lennon/McCartney bond is one that Harrison can’t undo, a force of nature that relegates him as the third-wheel in what could be interpreted as a musical love triangle. Despite the obvious, George, upon his return after a temporary departure from the band, continues to enthusiastically make noteworthy contributions to help refine the “numbers” and bring them to their eventual emergence from a song’s birth canal. That said, it is a bit perplexing that “All Things Must Pass” never became a Beatles record.

Yoko isn’t seen as the fire-breathing dragon who single-handedly blew The Beatles to smithereens (although I started to wonder if she might torch the mic with her ear blistering singing that probably had the dogs in the neighborhood running for cover). Instead, she comes off like a loving and supportive partner to John. Ringo is the affable brother whose primary goal is to make the others in the band happy while Paul wants more than anyone to preserve the band’s integrity and keeps its engine firing on all cylinders. But the others don’t share his unrequited love for the band – at least not to his level and there’s a moment during the film where we see Paul’s eyes well up when it becomes obvious to him that The Beatles shelf-life is beginning to come full circle. With George temporarily quitting, coupled with Lennon’s habitual tardiness, Paul looks dead into Lindsay-Hogg’s lens and says, “And then there were two”.

Could The Beatles have continued?

Absolutely! They could have each recorded individually and perhaps even curtailed their frenetic pace. Maybe they would have eventually toured together again. But lawyers and accountants got in the way. We’ve all seen how business can influence, even ruin friendships and families. The Beatles were no exception. When Allen Klein intoxicated Lennon with silver-tongue promises, John bought in and championed the sketchy lawyer whose markings were that of a snake-oil salesman, as his manager. George and Ringo followed. Paul never did.

And that really was the beginning of the end.

Years later Paul was proven to be right about Klein and his instincts saved The Beatles financially.

Still, as fans we’re left to wonder what could have been, post-Allen Klein. Mark David Chapman crushed those hopeful aspirations. Had John lived, it’s possible, perhaps even likely that these four lads from Liverpool would have eventually recorded together again. And while each of them accomplished much on their own, the magic they created together – that lightning in a bottle, would never be rediscovered as solo artists.

There’s something to that age-old credo, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts”.

And that whole is on full display for nearly 8 hours in Peter Jackson’s “Get Back”.